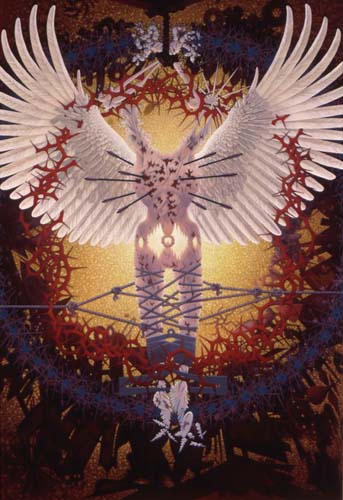

1982-83, acrylic on canvas

72 x 66 in.

Mains had his second one-man show at Houston's Graham Gallery in 1981. In September of the same year he moved to California. The paintings done through 1985 intuitively developed along Mains' "constructivist" tendencies; this period is represented by catalogue #'s 1-11 in this exhibition. In the painting from 1982-83 (catalogue #8), executed predominantly in blues and reds, a flux of linked rhombuses, intestinal/cloud forms, pointed plain and intricate ellipses, and other objects too numerous and diverse to classify appear to converge on a central circular form composed of writhing rose and turquoise strands. Within it, two V-shaped wedges hover in opposition, while between them a "cluster of energy" rotates against a distant dark and menacing void. Mains generates all his forms directly upon the canvas - there is no preliminary sketching apart from what appears on the picture plane.